19

May

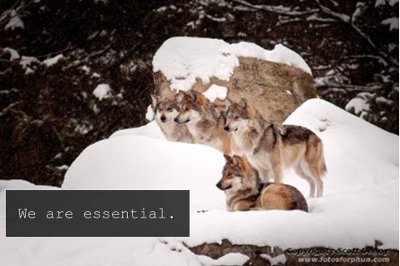

Editorial: Protect the Endangered Species Act

The most successful environmental legislation ever enacted faces new threats from Congress

A century ago an iconic, keystone species—the gray wolf—all but vanished from the continental U.S. Its loss was no accident. Rather it was the result of an eradication campaign mounted by ranchers and the government to protect livestock. Hunters shot, trapped or poisoned the wolves and received a bounty for each kill. Not even the national parks, such as Yellowstone, offered safe haven. Within decades the apex predator was nearly gone, a decline that triggered a cascade of changes down the food chain.

Today, however, in the 28,000-square-mile wilderness of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, 400 gray wolves roam free. The Yellowstone wolves are among the 6,000 or so gray wolves that now inhabit the lower 48 states thanks to the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The act was signed into law in 1973 to protect endangered and threatened plants and animals, as well as the habitats critical to their survival. The ESA has prevented the extinction of 99 percent of the 2,000 listed species. It is widely considered the strongest piece of conservation legislation ever implemented in the U.S. and perhaps the world.

Yet for years the ESA has endured attacks from politicians who charge that it is economically damaging and ineffectual. Opponents argue that environmental groups use the legislation to file frivolous lawsuits aimed at blocking development. Moreover, they contend that the ESA fails to aid species’ recovery. As evidence, they note that only 1 percent of the species that have landed on the protected list have recovered to the point where they could be delisted.

The latest assault comes in the form of the Endangered Species Management Self-Determination Act, a bill introduced by senators Rand Paul of Kentucky and Dean Heller of Nevada and Representative Mark Amodei of Nevada. The bill would, among other things, require state and congressional approval to add new species to the protected list—the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service do this now, based on the best scientific data available. It would also automatically delist species after five years and allow governors to decide if and how their states follow ESA regulations.

Senator Paul and others advocating for reform say that they want to improve the law to better serve imperiled species and local people. But their arguments are flawed. The reason why few species have recovered to the point where they can be delisted is not because the ESA is ineffective but because species take decades to rebound. In fact, 90 percent of the listed species are on track to meet their recovery goals.

In addition, lawsuits filed by environmental groups have led to many of the ESA’s accomplishments. The ESA may require a development project to make modifications to address concerns about listed species, but the benefit of the ESA to ecosystems outweighs this inconvenience to developers. The changes critics are lobbying for, while undoubtedly appealing to groups such as farmers and loggers, would cripple the ESA.

Yet the flaws of this bill do not mean the ESA cannot be improved on. For example, Congress should help the private landowners who choose to act as stewards of their land. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, about half of ESA-listed species have at least 80 percent of their habitat on private lands. Yet landowners have few incentives to preserve the habitats of threatened species. More financial and technical assistance needs to be made available to landowners who want to help protect the species on their property, as well as to people such as ranchers whose herds may be affected by the return of a species like the gray wolf.

Perhaps most important, conservation efforts must be updated to reflect what scientists now know about climate change and the threats it poses to wildlife. As temperatures rise, many more species will fall on hard times. Policy makers should thus increase ESA funding to allow more rigorous monitoring of wildlife and to protect more species.

Against the backdrop of budget cuts, setting aside more money to save animals and plants might seem like a luxury. Nothing could be further from the truth. Healthy ecosystems provide a wealth of essential services to humans—from purifying water to supplying food. We must preserve them for our own well-being and that of future generations.

This article was published in Scientific American on May 18, 2014.

**************************************************************************************************************

Would you like to help endangered Mexican wolves thrive?

Click here to learn how to influence decision makers to make changes urgently needed for the long-term survival and recovery of Mexican wolves.

Donate to support our work for Mexican gray wolf recovery.

Click here to join our email list for Mexican gray wolf updates and action alerts.

Photo credit: Scott Denny